Skiing down the highest mountain in Los Angeles

First came early weather reports, the forecasts of historic rain and snow headed for Los Angeles. Then came the storm itself, and by that time Andy Lewicky was too excited to sleep.

Checking the National Weather Service every few hours didn’t help. Lewicky kept scanning meteorologists’ Twitter feeds, hungry for any morsel of information he could spot.

“That way you can read the buzz as to how excited they are,” he said. “It’s hard not to get obsessed.”

The 55-year-old writer devotes himself to a peculiar hobby — discovering hidden spots for backcountry skiing in the mountains of drought-plagued Southern California. Could an epic cold front offer something truly extraordinary, an opportunity to charge down the slopes with a view of downtown in the distance?

Sunday morning, as sunshine finally broke through, Lewicky convened a group of like-minded friends at a McDonald’s in Tujunga for Egg McMuffins and eager chatter. Soon they headed up the road to nearby Mt. Lukens.

A group of skiers make their way up Mt. Lukens on Sunday morning.

(Andy Lewicky)

Skiers make their way home from Mt. Lukens on Sunday.

(Andy Lewicky)

It was the first time any of the men, in their 40s and 50s, could recall seeing Lukens, a 5,000-foot peak at the city’s northeast border, blanketed in so much white. Strapping skis, boots and poles to their backs, they began a four-hour hike to the summit.

“All the pressures, the traffic and smog … L.A. is not an easy place to live,” Lewicky said. “When I get to experience skiing and snow in this desert home I’ve chosen, it’s a special thing.”

Backcountry is a niche subset of the skiing world. It exists apart from pricey resorts, high-speed lifts and groomed runs, attracting a breed of skiers who hunger for a natural setting of rocks and trees with no one else in sight.

That can mean trekking all day to make but one run down an isolated couloir or a bowl. It can mean braving avalanches and other dangers that lurk above, and below, the surface of unmanaged terrain.

A small but devoted cadre of local skiers devotes itself to finding such opportunities in ranges such as the San Bernardinos, San Gabriels and San Jacintos. Lewicky, whose SierraDescents.com blog chronicles this passion, calls it “living with one foot in two different worlds.”

Skiers make their way to the summit of Mt. Lukens on Sunday.

(Andy Lewicky)

Reeling off statistics from memory, he says few people realize that Southern California has an impressive “peak prominence,” the combined distance from base to summit along its various ranges. But those spots seldom get enough snow to ski.

“Scarcity spawns stoke,” said Preston Lear, a West Hollywood therapist who skis with Lewicky. “When there is snow, there are people willing to hike for it.”

No one in Sunday’s group of five had attempted Lukens, which is part of the Angeles National Forest and ranks as the tallest peak within L.A. city limits. On the trip there, Matt Dixon, a civil engineer, said he “almost drove off the 2 Freeway” staring at all that white.

Matt Dixon skis along the east ridge of Mt. Lukens with the downtown Los Angeles skyline in the distance.

(Andy Lewicky)

Though Lukens is fairly tame and accessible compared to other places they have ventured, Lewicky and his crew took an array of safety equipment, including shovels and avalanche transceivers.

Skiing in the backcountry requires traversing narrow ridges with skis chattering across ice and snow. Every descent is a minefield of protruding rocks. Even if no avalanches break loose, skiers can be swallowed by “tree wells” — deep pockets of loose snow surrounding evergreens — and die from suffocation.

Al Preston packed a collapsible metal pole used to probe for fellow skiers should they get buried. “I’ve never used it,” the South Pasadena engineer said. “My goal is never having to.”

Preston Lear skis off the east ridge of Mt. Lukens with the skyline of downtown Los Angeles in the distance.

(Andy Lewicky)

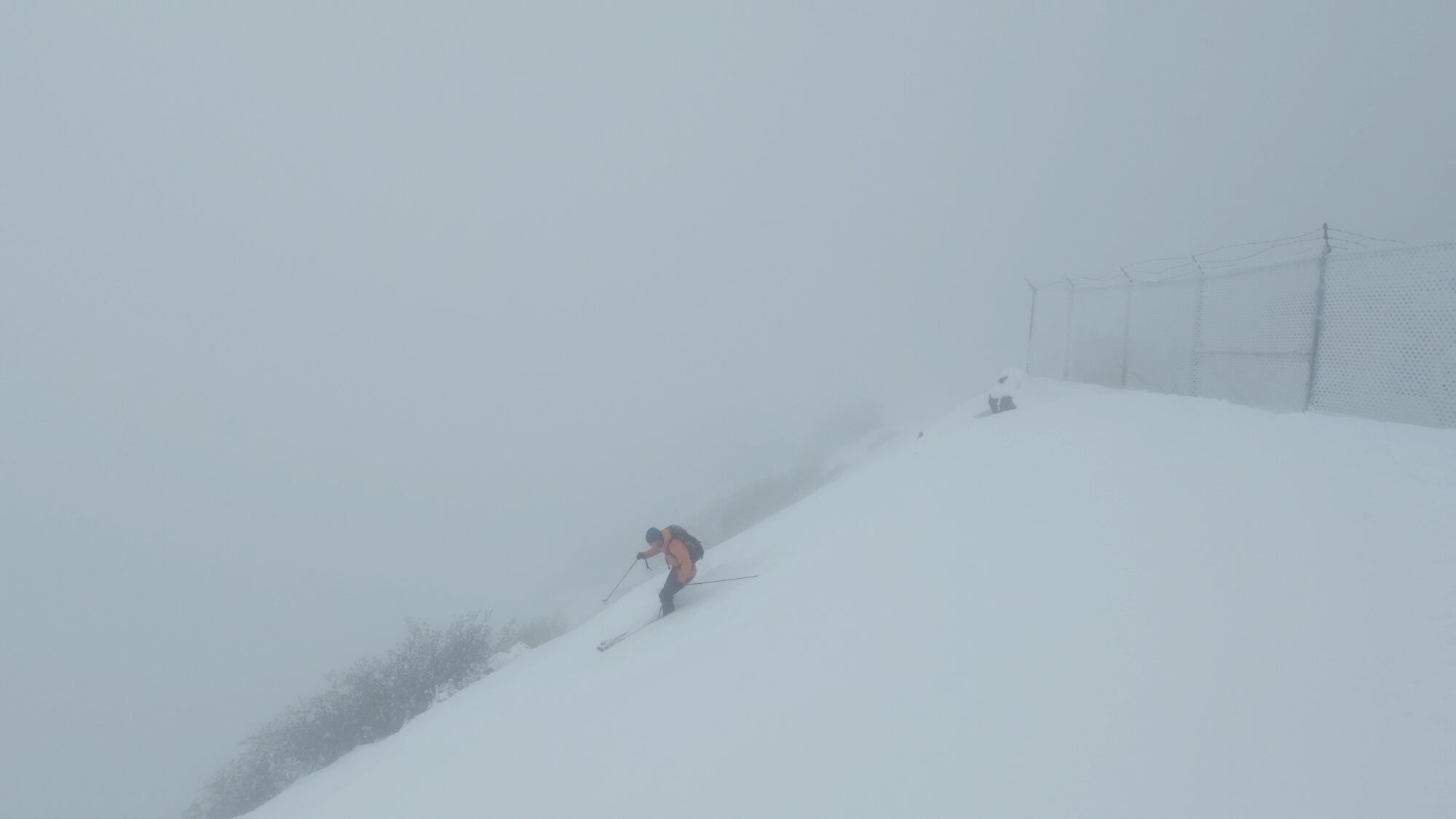

Preston Lear begins his descent from the fog-shrouded summit of Mt. Lukens.

(Andy Lewicky)

Sleuthing is part of the thrill for backcountry skiers living in a Mediterranean climate that tends toward semi-arid. Summer hikes double as research as they scan the mountains for topographical features that might be skiable with enough snow.

The uninitiated might scoff at the effort required for one relatively short run.

“The going-up is actually fun,” Lewicky said. “You have the mountain to yourself, very rhythmic and peaceful.” Every step closer to the peak, he added, “obviously builds a lot of anticipation.”

It helps to have alpine touring gear made light for carrying. Bindings can be switched from downhill to cross-country mode with heels detached. Temporary “skins,” made from mohair and nylon, can be attached to the bottoms of skis for pushing along flats and inclines on the way up.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

Sunday’s climb began under a bright sun that softened the morning’s chill. The snow quickly became several feet deep, slowing progress.

“It was weighing down the brush,” Dixon said. “We had to crawl through in some places.”

The situation worsened along a curving ridgeline at a higher elevation. Another front was moving into the region, the first clouds stacking up against Luken’s west face. That sought-after view of downtown was now obscured in grayish haze.

“We kind of shook our fists at the sky,” Lewicky said.

The group waited awhile at the summit, eating snacks, hoping the weather might clear. They skied the west face several hundred vertical feet to a crossing fire road, then decided to climb back up and weigh their options.

“You have to see what the mountain gives you on any given day,” Dixon said. “It’s more about the adventure than necessarily just the skiing.”

A long fire road descended eastward from the peak. Perhaps it could lead them out of the clouds.

Lewicky’s benchmark for great adventures dates to 2008 when, on a hike through the San Gabriels, he spotted an unfamiliar couloir — a steep chute bordered by rock on either side — in the distance. Narrow and hazardous, it piqued his curiosity.

Maybe skiable, he thought. Maybe not.

Topographic maps pinpointed the spot at 7,500 feet up the north face of Iron Mountain, but there was a problem. The San Gabriel River, bordering that side of the mountain, blocked any direct ascent. Lewicky got to work looking for another option.

Matt Dixon flies off a ski jump on the east side of Mt. Lukens.

(Andy Lewicky)

An approach from the backside would require climbing 8,000 feet to the peak, descending partway, skiing and then taking the same route back. The roundtrip of 18,000 vertical feet was daunting.

Over the next two years, Lewicky and some friends tried summiting an adjacent peak and traversing across, but the connecting ridgeline proved too risky. Turning back, they ran into another skier with the same idea.

David Braun is a JPL engineer known for exploring some of the region’s most remote spots. Remote enough that he once had a golden eagle dive at him.

“We looked each other in the eye,” he recalled. “Then he figured I wasn’t something to eat.”

It made sense for Braun to join forces with Lewicky to conquer Iron Mountain. Their quest would result in a short film called “The Couloir to Nowhere.”

Resigned to taking the long way, they set out in spring 2010, climbing the mountain from the south, spending the night there, then summiting and reaching their destination the next morning.

Rivulets and rocks made the couloir treacherous. Backcountry skiers are best going one at a time; the others hang back in case something catastrophic happens.

Slowly, they picked their way down, making quick jump turns within the narrow, walled space, stopping to consider the lip of a slight rise ahead. Braun asked: “Is that a cliff or a mirage?”

Matthew Testa skis down the west face of Mt. Lukens in white-out conditions on Sunday.

(Andy Lewicky)

After about 1,500 vertical feet, the couloir narrowed and made a sharp bend. The men stopped and, breathing hard, decided they had gone as far as possible. Lewicky thanked Braun.

“I wasn’t going to do it alone,” Lewicky said. “And nobody else would do it with me.”

Choosing the eastern fire road on Mt. Lukens quickly paid off.

Within minutes, it led to a side of the mountain protected from the weather. The view cleared to reveal the San Fernando Valley below. Downtown skyscrapers glittered in the sun and, beyond that, the ocean looked golden.

“It was amazing,” Dixon said. “You could see several of the Channel Islands.”

Al Preston and his friends play around on a ski jump they formed on the east side of Mt. Lukens on Sunday.

(Andy Lewicky)

The group lingered to snap photos and fool around, building a hump of snow for taking jumps. But they couldn’t hang around too long, not with late afternoon approaching and their planned half-day trip stretching toward 10 hours.

The fire road ran seven miles with flat spots and wet snow that made for sluggish going. It took them far astray, terminating at a U.S. Forestry Service station along the 2 Freeway, where an Uber could accommodate only two of them.

Arriving back at their starting point after dark, Lewicky pulled off his ski boots and jacket, hurrying to get in his car and retrieve the others. He looked exhausted while explaining all that had gone awry, but smiled all the same.

“It was a spectacular day,” he said.

A historic storm. A chance to explore new terrain. A new place to ski in the wilderness, in a city where that seems improbable.