How a basketball player who was deaf and had autism changed Cerritos College

“Put him in, coach!”

With barely a minute remaining in a blowout of Porterville College in mid-December, Cerritos College basketball coach Russ May was faced with a heart-tugging dilemma.

“C’mon coach, let him play!”

Sitting at the end of his bench was Kade West, a 20-year-old who is deaf and autistic. His hands were folded in prayer. He was silently pleading to play in his first game.

West had been hanging around the fringes of the junior college team for more than a year, trying to impress, hoping to belong, shooting countless shots each day at a rickety basket in the alley behind his house, showing up for every practice at the Cerritos gym and playing until it had emptied.

May was so awed by his resilient effort that he added West to this season’s roster to serve as a bench-warming inspiration. West celebrated the awarding of his new No. 15 uniform as if he had just joined the Lakers.

There was one problem. Because West’s special needs prevented him from completing the required 12 academic units required to play, he needed an eligibility waiver from the California Community College Athletic Assn. Despite the family’s best efforts, the waiver appeal had not yet been processed. When the game against Porterville had reached its final 1:39, West was still not yet officially allowed to play.

Yet suddenly, that didn’t seem to matter. The team’s players and assistant coaches and even fans were begging for one shining moment.

“Coach, coach, put him in!”

Kade West, left, a deaf and autistic athlete at Cerritos College, goes up for a shot during a practice session with coach Russ May.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

May looked down at the end of the bench and sighed. The game was in Visalia and West’s family had paid his way so he could travel with the team. This could be the fulfillment of a dream of a player who didn’t let an inability to hear or speak or read above a third-grade level stop him from playing his way into the Falcons’ hearts. His teammates would applaud him by waving both hands in the air. The Cerritos fans would cheer him by stomping their feet on the bleachers so he could feel the vibration.

May couldn’t help himself. He knew Kade West wasn’t officially on the team, but, at that moment, no one on the team was more important. May looked down to the praying figure. He motioned to the court. It was a gesture he knew West would understand.

“Get in there, Kade.”

West shot out of his seat. He raced into the action. He sprinted up and down for those final moments while working up the sweat of a lifetime. He took one shot, and missed it, but by the time Cerritos had finished off an 81-60 victory, he was being cheered by the tearful Porterville fans, hugged by everyone in sight, and celebrated for representing all that is right about this increasingly cold world of sports.

“I know the rules, but the human part of me took over,” said May. “It was an incredible moment.”

Followed, sadly, by a series of even more incredible moments.

May was suspended for a game. Cerritos was ordered to forfeit the victory. And West was temporarily stripped of his uniform.

Kade West with coach Russ May at Cerritos College.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The extra loss cost the Falcons a first-round bye in the postseason tournament, where they distractedly lost that opening game to lower-seeded Copper Mountain in double overtime, their sterling season collapsing under the weight of the kindest of gestures.

The CCCAA had dropped the hammer, Cerritos College had administered the blow, and what was once so beautiful became broken.

May is still stunned.

“Yes, I broke a bylaw, but is this what our society has become?” he said. “Shouldn’t this be something we celebrate?”

Lucy Favro, West’s great aunt and caretaker, is still disheartened.

“It was such a beautiful moment, Coach May and the team saved Kade’s life, and then…how could that have happened?” she said.

Kade West still cries.

“It’s all my fault,” he signed.

In an alley behind a Long Beach bungalow, the definition of determination can be found on the bodies of a light gray Kia and dark gray Honda.

The cars, parked next to a basketball goal, are riddled with pock marks.

Kade West plays here.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Kade West demonstrates how he plays basketball at his home in Long Beach.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

“You can see how much he practices by the number of dents on the hoods,” said his cousin and guardian Sasha Svimonoff, smiling. “But, you know, they’re just cars.”

This is where West, a bearded 5-foot-10 force of nature, retreated in the spring of 2021 upon the death of his mother Dijana from bladder cancer.

He had lost the woman who raised him. He was lost in a world that didn’t quite know how to handle deafness and autism. He had no close friends, only bad childhood memories.

Growing up in Long Beach, he attended schools that literally strapped him down in his school-bus seat to control him. Despite the best efforts of his single mother, he had bounced around from classroom to classroom, passed off from one wretched situation to another by those unable to deal with his unique condition.

He finally found stability during his high school years at the Learning Center for the Deaf in Framingham, Mass. However, when he returned home upon completing the program, his mother was dying and his options were limited.

“He had been through a lot of trauma,” said Favro. “He needed something to help him survive.”

He found that escape in basketball, a sport he began playing as a 15-year-old. He loved it because it was a sport he could practice alone, a place he could be judged only by his effort.

“Basketball leveled the playing field,” said Svimonoff. “Basketball was a way he could communicate.”

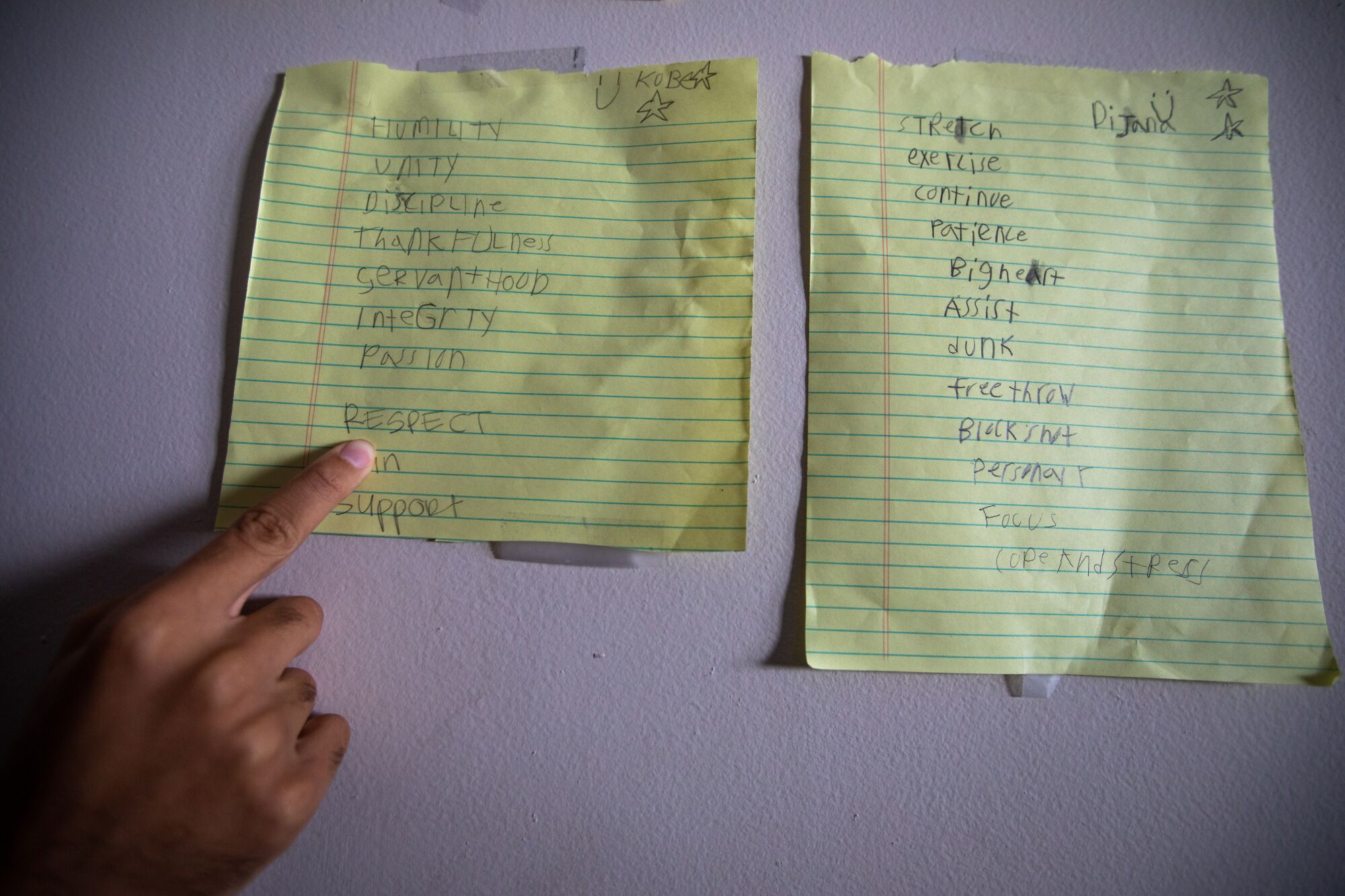

Kade West points out the goals he has taped to his bedroom wall at home in Long Beach.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

Upon his mother’s death, he began playing so much, he would dribble the air out of his weathered basketballs. Soon the television in the bungalow’s family room was constantly tuned to YouTube videos of 15-year-old Lakers games. Soon a list of traits inspired by Kobe Bryant was carefully printed on a piece of yellow note paper taped to his wall, ideals like humility, unity, discipline, thankfulness.

“I love basketball, I adore it, it’s my girlfriend,” he recently signed. “Basketball is my whole world.”

Then, that summer, West’s family signed him up for a Cerritos College basketball class taught by Russ May, and the Falcons joined that world.

“He came up to me and said he wanted to play in the NBA,” said May. “And he worked like it.”

Through interpreters provided by the school, West would grill May and his coaches about how he could improve, then he would stay late after class to hone those skills. He joined several recreation leagues around Long Beach. When the Falcons began practice, he began showing up with the team, chasing balls, helping on drills, an unofficial manager.

“Kade worked harder than all of us,” said Jalen Shores, a sophomore point guard. “He would be there an hour before us, stay an hour after us. The love he has for basketball, he worked super hard, we were feeling for him.”

Kade West watches interpreter Antonio Beltran use sign language while practicing.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

He stayed on the fringes of the team the entire 2021-22 season and remained with them last summer when he made a decision.

“He cut his hair, shaved his beard, and said he wanted to look nice because he was trying out for the team,” said Favro.

How could May put him on the roster? How could he not?

“He outworked everybody, he had so much hustle, so much determination, what choice did I have?” said May. “Kade had earned his spot.”

He warned West that he might not play very much. He didn’t even give him a uniform until after they had played four games. But, goodness, that uniform … West was so excited he grabbed whatever he was handed without checking the size.

“He comes home and it’s a XXL and he’s swimming in it,” said Svimonoff. “He doesn’t care. He puts it on and announces how good he looks.”

The family applied to the CCCAA for the waiver appeal on Nov. 17 with the understanding that Cerritos already possessed the necessary paperwork. They were later told they needed to provide transcripts, a letter detailing his necessary accommodations and an explanation of his educational capabilities, which they did on Dec. 3.

The CCCAA and its Disability Appeals Board has a combined 12 working days to render a decision. When the team took its first road trip of the year to Visalia in mid-December, even though the Falcons had already played 10 games and the family had initially applied a month earlier, the waiver had not yet been granted.

“I just wanted someone to hear Kade’s story. But nobody would listen.”

— Russ May, on his appeal to the CCCAA

May informed the family that he was not yet eligible and should stay home. West went anyway, paying his own expenses just for a chance to hang out on the road with his guys. This is the same welcoming group that once invited West to join them on a bowling outing, marking another milestone.

“Kade told us it was the first time anybody had ever invited him anywhere,” said Favro.

He wanted to be in Visalia. His teammates wanted him to be in Visalia. And with 1:39 remaining and his team leading Porterville by 20, May wanted West on that court.

“I just thought, isn’t this what sports is all about?” he said.

After West’s brief appearance, he FaceTimed several members of his extended family with the dazed smile of a champion.

“He was over the moon,” said Favro. “Those two minutes meant the world to him.”

Kade West laughs with teammates while using sign language during practice.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Yet that 1 minute and 39 seconds also meant enough trouble to damage a season.

First, the CCCAA suspended May for a game, the reasoning explained by executive director Jennifer Cardone in an email response to this columnist’s questions.

“The suggestion to suspend Coach May for at least one game was made to Cerritos College and the South Coast Conference after I learned that the coach intentionally played a student-athlete while ineligible…” Cardone wrote.

May did not argue.

“I wasn’t happy about it, but I accepted it, I understood it, fine, we move on,” he said.

But then it got worse. Four days after the Porterville game, when West showed up at the school for a trip to San Diego County, a school official refused to give him his uniform.

When the other players weren’t looking, West broke down in tears.

“Kade is in a crack in the system, nobody knows what to do with him. The only people that have really shown him patience, respect and allowed him to be himself are the Cerritos basketball team.”

— Sasha Svimonoff, Kade West’s cousin and guardian

“He was heartbroken,” said Svimonoff. “He thought they had thrown him off the team. He just couldn’t understand.”

Rory Natividad, dean of athletics at Cerritos College, explained that the school was simply following the directive of the CCCAA.

“Unfortunately, the situation we’re in, we had to respond, obviously to the bylaws,” he said, adding, “Our normal process is that we don’t issue uniforms until they’re eligible…after we got the letter from the commissioner, we obviously had to respond at that point until we got the clearance.”

West was denied the uniform for two games before he was cleared for the rest of the season. But wait, it gets even worse. After assuming they were finished paying the price for their good deed, the Cerritos team was later ordered to forfeit the Porterville game. The loss eventually dropped their final record to 19-10 and lowered their postseason enough to cost them a first-round bye. West was certain he had caused all of it.

“He was devastated,” said May. “He was stigmatized.”

Cardone cited the precise wording in the association bylaws that mandates a “forfeiture of the contest,” in the event of “participation of an ineligible student-athlete.”

“The men’s basketball program intentionally played an ineligible student-athlete,” she wrote.

Kade West shoots a free throw while practicing at Cerritos College.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

May had accepted the suspension, but the forfeit was too much. He sent emails to each of the 12 CCCAA board members. He didn’t receive one response.

“I just wanted someone to hear Kade’s story,” he said. “But nobody would listen.”

In her email, Cardone said her association supports student-athletes like West.

“Russ May and Cerritos College are to be commended for providing Mr. West an opportunity to be a part of something as valuable as being a member of a team,” she wrote. “The inclusion and compassion showed by the coaches and student-athletes exemplifies what we’re trying to do.”

If that is really the case, in Kade West’s situation they miserably failed.

West quickly recovered from the humiliation. He always does. He finished the season with five appearances for 10 total minutes while sinking two baskets and a free throw.

“What happened wasn’t fair at all, but no hard feelings, and Kade kept working,” said Shores. “Every day at practice he would smile at us, wave to us, hug us, give us high fives, bring the same energy every single time.”

There are a couple of video snippets of his triumphant plays. One of them is hard to watch. As the play proceeds, the videographer’s hand begins to shake.

“The person taking the video is stomping their feet like the rest of the crowd,” said Svimonoff.

West plans to play during his sophomore season. May plans on having him back. They will have to endure the waiver appeal process again. They say it’s worth it.

“I don’t guarantee any players spots on next year’s team but let’s just say, it will be difficult for me to foresee a reason not to have him on the team,” said May, who will be entering his 15th season.

West said he will earn that spot.

“Coach May cares for me,” he signed. “He won’t give up on me. I’ll practice hard and do the best I can.”

Kade West uses sign language while standing next to Cerritos College teammate Malik Johnson.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

May said if faced again with the choice of playing an ineligible West, “I wouldn’t do anything different.”

Indeed, by summoning that praying player at the end of the bench, May did more than just make a substitution, he helped change a life.

West is now working with a teacher on marketing a line of athletic clothing adorned with the logo K.A.D.E…Keep Advocating for Deaf Empowerment.

“Kade is in a crack in the system, nobody knows what to do with him,” said Svimonoff. “The only people that have really shown him patience, respect and allowed him to be himself are the Cerritos basketball team.”

After the final game of the season, after May had delivered his final locker room speech and the final tear had been shed, a couple of kids started shooting baskets in the Cerritos gym.

West returned to the court in his street clothes and started playing with them. His family was waiting in the stands to take him home. He kept playing. And playing. And playing. They sat there for an hour. In a world that had now been opened, he once again closed down the gym.

“I love my team,” Kade West signed. “And my team loves me.”