When and why the epidemic sparked a fitness craze through dance

A bubbly ball of energy in a crop top, ’80s-style hot pants and platinum mullet, Emilia Richeson-Valiente shakes her hips to the B-52’s “Private Idaho” inside a studio space at Live Arts Los Angeles in Glassell Park. Behind her, people follow her moves in joyously chaotic ways — some burst into air guitar solos, while others let out the occasional primal scream.

“Take the patterns of movement you like and f— the rest!” she instructs.

At Pony Sweat, the dance fitness company that Richeson-Valiente created, there’s a distinctly anti-perfectionist vibe. It’s not about technique or hitting every beat or what you look like doing the moves. Instead, it’s about having a safe, supportive community where people can lose themselves in the music and feel all the feels.

“We come and commune here and everything explodes and it’s beautiful,” said Alyssa Aramanda, a participant at a Wednesday class.

Pony Sweat participants, a.k.a. ponies.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Follow-along dance fitness classes — group workouts in which participants need no prior dance experience and simply follow the teacher’s moves — are cropping up in studios across L.A. The accessible format gained popularity during the pandemic. In the safety of their living rooms, garages or patios, people logged on to Zoom and other portals and danced with strangers around the world to help process the loneliness, grief and anger they were feeling.

“So many of us were really having to face ourselves and be alone with ourselves,” Richeson-Valiente told me after class. “Dance fitness was an accessible medicine for people — a way to get out what we were really feeling and experience some joy.”

With Pony Sweat community members (a.k.a. ponies) telling Richeson-Valiente that the online classes were becoming a critical part of their keeping-it-together routine, she and Michella Rivera-Gravage, the company’s operation lead, scrambled to build out the website for a flock of new visitors. It was important to them that their ponies, some of whom lacked a queer-friendly community in their neighborhoods, could maintain their connections.

While the shift to online classes was no doubt a means of survival, it also changed the trajectory of the movement, propelling the total number of people who have taken a class by 58%. Pony Sweat’s Instagram following has more than doubled since early 2020.

Isaac Prado dances during a Pony Sweat session at Live Arts Los Angeles in Glassell Park.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Richeson-Valiente isn’t alone. As dance instructors took their classes online, many were able to pick up new students from all over the country. “It has been really incredible,” says Clara Siegel, chief executive of Seattle-based Dance Church, which expanded the number of people who had taken its classes from 40,000 pre-pandemic to 144,000 as it shifted back to in-person. Sadie Kurzban, founder of New York-based 305 Fitness, found “two new revenue streams” during the pandemic: a virtual at-home platform and an instructor certification program.

This summer, Richeson-Valiente returned from a Pony Sweat tour to meet both new and longtime ponies from Boston, New York City and Philadelphia. She also made a stop in Littleton, N.H., close to where her family is from.

That was a homecoming of sorts. For Richeson-Valiente, being alone in her bedroom and dancing to music by the Cure and other ’80s artists was her way of dealing with difficult emotions as a goth teen. A self-taught aerobics fan who was inspired by Jazzercise, Zumba and classes at the now-closed Sweat Spot in L.A., she continued to be fueled by dance and often talked about teaching dance aerobics while working Saturday kitchen shifts at a local restaurant. In 2014, her friends surprised her by pitching in to rent her a studio space where she could hold classes. One friend, Noah, helped dream up the name Pony Sweat, for its relation to dance, the queer community and Richeson-Valiente’s propensity to really sweat.

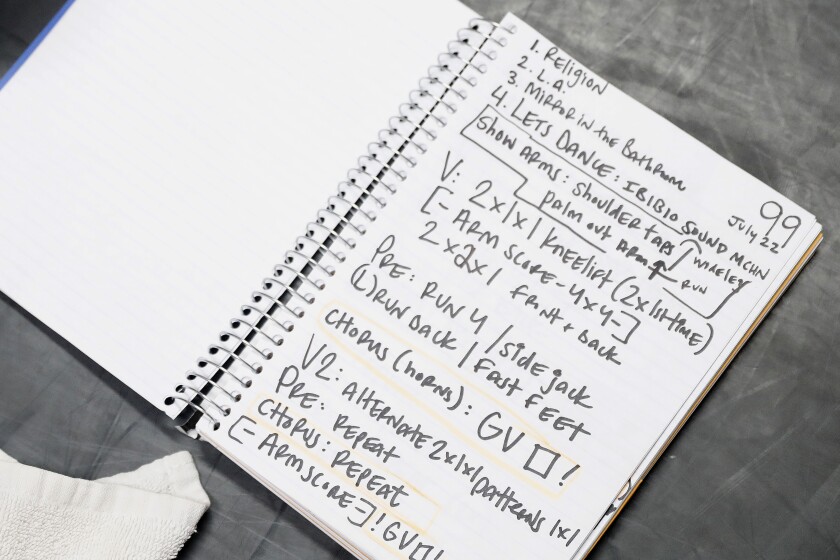

Emilia Richeson-Valiente’s notes for a Pony Sweat class.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

“It was, in a way, a reclamation because I had been so ashamed of my big sweating,” she said with a laugh.

These days, Pony Sweat’s mixtape changes every month (at the class I attended, songs ranged from Judas Priest’s “Turbo Lover” to Le Tigre’s “Eau d’ Bedroom Dancing”).

Richeson-Valiente and Rivera-Gravage hope to expand Pony Sweat’s community both online and in-person through events, collaborations with other artists and organizations; a community action arm, Ponies Against Fascists; as well as new offerings of “video rentals” and the On Our Own But Never Alone (OOOBNA) monthly dance subscription. They also recently launched a Pony Sweat server on Discord, where ponies can connect with one another when class isn’t in session. Another recent class addition: aural aerobics. It’s a radio class with no visual element — just music and Richeson-Valiente’s vocal guidance.

All of it is evidence that dance aerobics is finally getting the attention it deserves after being dissed for so many years by the fitness community.

“Folks are finally approaching dance fitness like I like to think of it, which is emotive expression,” Richeson-Valiente said.

She calls her dance space “fiercely noncompetitive” and embodies that spirit with every pivot, body roll and booty shake.

Emilia Richeson-Valiente leads a Pony Sweat class. “Take the patterns of movements you like,” she instructs, forswearing perfection.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

“My journey with dance was that it was really difficult for me as a young person and throughout my life to give myself permission to not be good, or to not look like the teacher,” Richeson-Valiente said. “The point of Pony Sweat is for people to discover freedom of movement and expression in their own bodies.”