The mullet is a hairstyle that will not die.

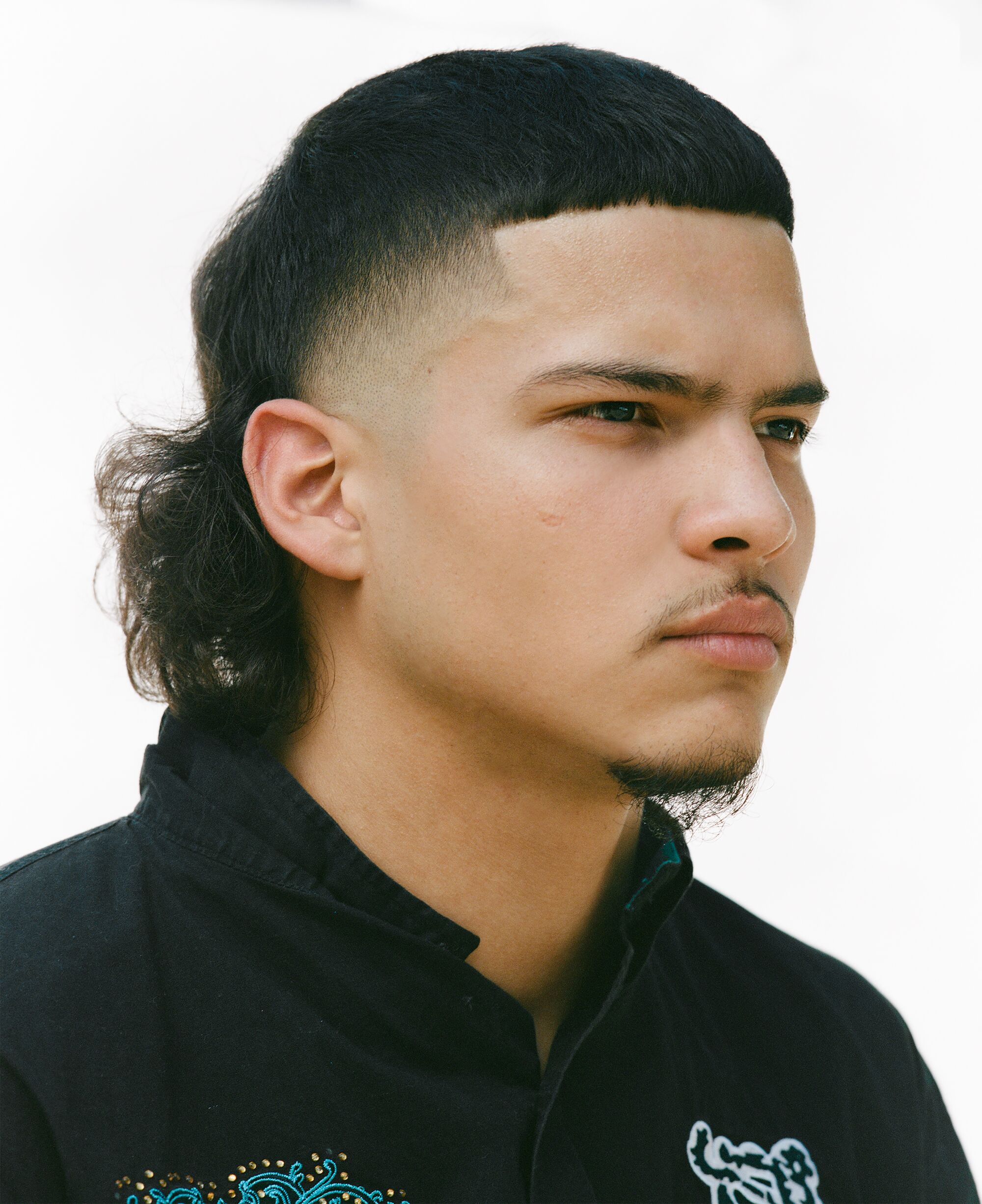

Is everything we call a mullet actually a mullet? Who decides what is a real mullet and what’s actually stolen valor?

(Fabian Guerrero/For The Times)

This story is part of Image Issue 14, “Elevation,” where we examine beauty as a state of being, a process of realization. Read the whole issue here.

“Do you like my mullet?” my friend Alana asked me over lunch at Little Dom’s recently. I had to think deeply before responding. I didn’t immediately clock her hairstyle — curly, a bit unkempt, voluminous — as a mullet, but it’s one I’ve seen around Los Angeles more and more recently on a lot of different kinds of people.

Naturally, I told Alana I loved it. One, because I legitimately do, but also because this is L.A. We love everything our friends do, even if we don’t. Who here wants a conflict when it could just be talked over with a therapist later? Regardless of whether or not I loved the haircut, Alana claimed her hairstyle as a mullet, even if I wasn’t sure.

But is everything we call a mullet actually a mullet? Who decides what is a real mullet and what’s actually stolen valor?

We all have different associations and expectations about what a mullet is or should be.

(Fabian Guerrero / For The Times)

The mullet is, simply, a short haircut finished off with long, flowing locks in the back. That seems simple enough, but there’s a whole galaxy of variation within that definition. We all have different associations and expectations about what a mullet is or should be. Much of that is related to class. For decades, it was seen as a low-rent haircut that may or may not have been perpetrated upon you by your mother using the cursed late-night infomercial monstrosity the Flowbee. For the uninitiated, the Flowbee was a device you plugged into your vacuum cleaner to cut your hair faster. Yes, you can still buy one.

Because of the class associations, mullets were considered uncouth and undesirable for most of my lifetime. Sort of like a less expensive Jheri curl, but for white people. The Jheri curl was a sign of extreme abundance in the Black community. If you could afford activator and managed to not set yourself on fire every time you left the house, you must have made it out of the hood. The mullet, on the other hand, was a sign that you were trapped and might never get out.

The mullet is the haircut that refuses to die. It dominated the tail end of the 20th century, fell into clutches of derision and acidic irony by the late ’90s and suffered a variety of pop culture indignities for most of this century. It’s the haircut from the David Spade movie “Joe Dirt.” Silly, low-class and, worst of all, hideous to look at. That was the rap on it for years, but somewhere around the start of the pandemic — when professional haircuts became illicit, speakeasy-style clandestine hookups that could end up putting you in the hospital — comparatively haphazard hairstyles like the mullet slithered back into cosmopolitan America’s good graces. “I love your mullet” can be heard throughout the hip neighborhoods of Los Angeles. It might be the most popular greeting amongst a certain type of artistically minded individual since the stern head nod. There’s even a nascent competitive mullet scene. The U.S. Mullet Championships was formed in 2020 to honor the best-in-class hairstyles. A cut once deemed déclassé is now at the forefront of chicness.

The mullet is the haircut that refuses to die.

(Fabian Guerrero / For The Times)

Using the term “mullet” to describe a hairstyle is a somewhat new phenomenon.

(Fabian Guerrero / For The Times)

Using the term “mullet” to describe a hairstyle is a somewhat new phenomenon. The first instance of the use of the word was recorded in 1994 in the Beastie Boys song “Mullet Head.”

Until then, it was most commonly called “hockey hair,” since it was embraced by athletes like Wayne Gretzky and Jaromír Jágr. Other sports stars wore mullets back in the 20th century, though. Los Angeles was the home for Mike Piazza’s mullet when he played for the Dodgers. Showtime Laker Kurt Rambis’ hair would venture close to mullet territory here and there in the ’80s. The mullet was perfect for athletes because it combined the masculine quality of the short top half with the flowing tails on the bottom. It stuck out of a helmet like peacock feathers. It flapped in the breeze while you ran. It was the kind of thing you might see on a trucker or a construction worker, which suited the blue-collar associations some athletes like to cozy up to despite their multimillion-dollar salaries.

But the hairstyle itself is popularly attributed to David Bowie in 1972. Bowie adopted the proto-mullet style for his Ziggy Stardust alter ego: bright red, spiky in the front and cascading gently onto his neck. Bowie gave the mullet androgynous, counterculture swag.

A recent New York Times article described the mullet being such a freak-o signifier that people would cross the street to avoid you if you wore one, but esteemed hairstylist Guido Palau has been playing with lengths and textures for years, and one of his favorite looks is the mullet. Paired with the right model and outfit, a mullet can look incredibly chic. That’s thanks to Bowie, Joan Jett or the dance-punk singer Peaches, who’s worn more varieties of mullet in her career than most of us even realized existed.

The curly mullet you see east of Western Avenue defies gender and recalls sexual liberation icons like Bowie and Peaches.

(Fabian Guerrero / For The Times)

The modern mullet says: “Accept me as I am.”

(Fabian Guerrero / For The Times)

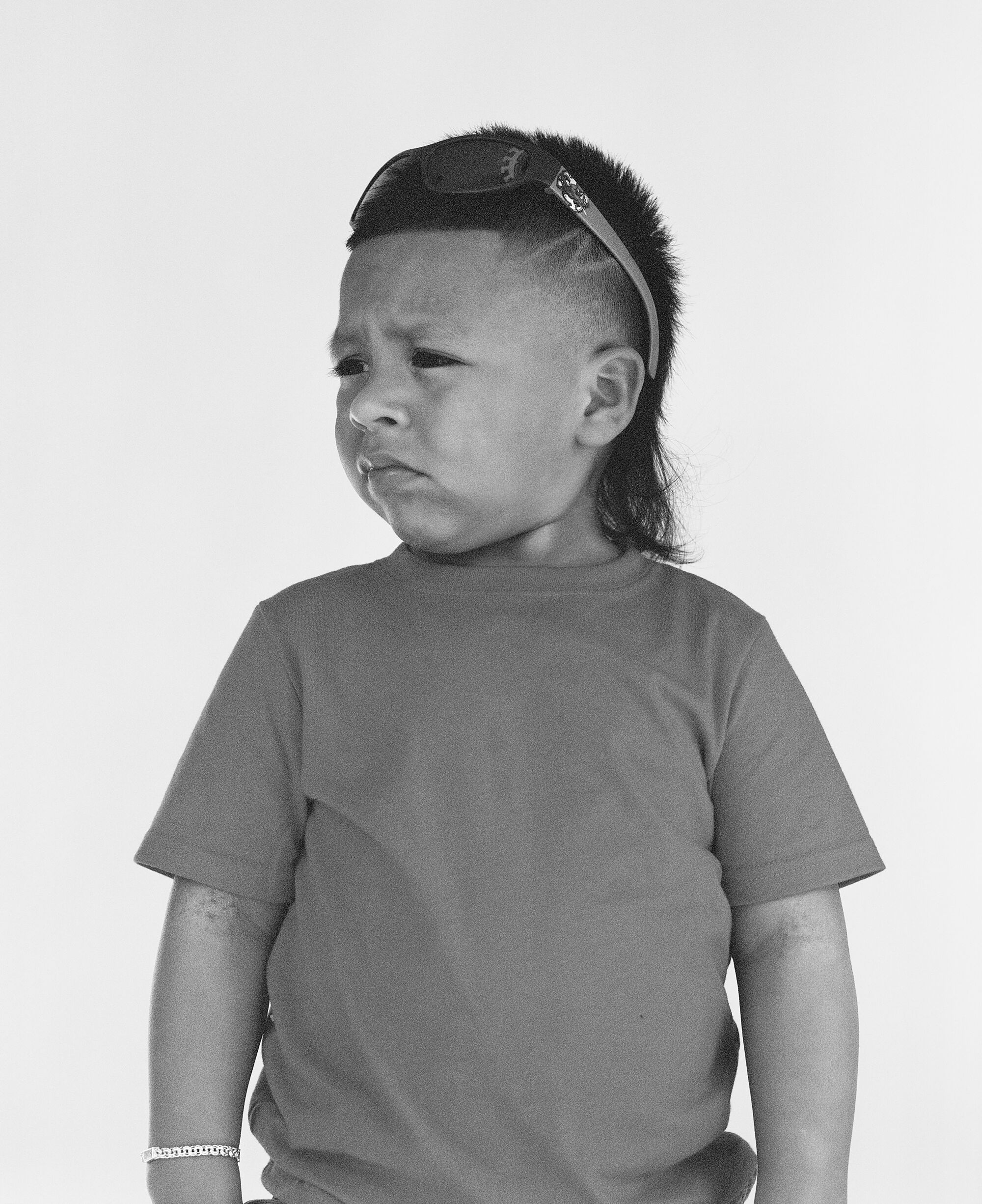

The most popular mullet of today isn’t the spiky Bowie version or the luxurious muskrat look from “Joe Dirt.” It’s a curly, haphazard style that’s been occasionally attributed to Ella Emhoff, the daughter of Vice President Kamala Harris’ husband, Doug Emhoff. Ella’s a model and New York socialite with a penchant for wearing collegiate, dowdy clothes that the New York Times referred to as “Wes Anderson chic” around the time of President Biden’s inauguration. Mullets are not exactly the haircut of the ruling class, which is why when Emhoff wears it, there’s a healthy tension that intrigues people.

The bouncy, curly mullet that Emhoff wears is softer and more feminine than the traditional buzz of the OG mullet. Maybe that’s why it’s been adopted by all types of people across the spectrum of gender in the last few years. This is a hard time we live in. War, social unrest, rampant disease and inequality are ever-present. Misogyny and homophobia — and racism for that matter — are considered by many to be acceptable political platforms in the United States. Softness in style is a response to that. Men can wear skirts and blouses and delicate fabrics like silk. Masculinity can be a pose instead of a strict requirement.

The curly mullet you see east of Western Avenue defies gender and recalls sexual liberation icons like Bowie and Peaches. It’s riding a ever-cresting wave of empowerment across the sexual spectrum in Los Angeles, a place that’s always prided itself on being at the forefront of countercultural movements (even if the city government itself isn’t always quite so liberated).

Mullets will never die because the spirit of what they represent won’t either.

(Fabian Guerrero / For The Times)

The symbolism is powerful, but it also looks easy. My friend’s mullet doesn’t have the bourgeois trappings of a $200 Beverly Hill salon special, nor does it have the casual extravagance of a $50 blowout with a side of champagne from Drybar. It’s the antithesis of the hair straightener industrial complex that tells Jewish women and people of color, among others, to spend money to achieve a platonic ideal of flatness. It conjures up thoughts of Melanie Mayron in Claudia Weill’s 1978 cult classic, “Girlfriends.” That’s not exactly a mullet, but the unadorned curls of her hair framing her bespectacled face and unisex outfit are exactly what so many of us are striving for. The modern mullet says “Accept me as I am,” even if that look actually took a while to put together.

Mullets will never die because the spirit of what they represent won’t either. It’s a style that can be a bridge between the working class and the artist class, the masculine and the feminine, and the business and the party. The grand duality of existence is buried under all that hair, if you look close enough.

More stories from Image