She breaks records pursuing underwater “ghosts” with a spear almost as big as her.

Mitsuki Hara is hiding amid the undulating kelp forests 30 feet below the surface of the ocean. In her arms is a 4-foot-6-inch speargun — almost as tall as she is — that she’s training on white sea bass, the elusive “gray ghosts” of California.

The real fight begins after she pulls the trigger. The pierced silvery bass fights to escape both its hunter and the shiver of soupfin sharks starting to stalk the bleeding fish. Tightening the window further, Hara hunts on a single-held breath. This gives her just about 90 seconds to work with each time she plunges into the murky Pacific.

On this hunt, the fourth free dive does it, and Hara finally emerges with the 73.4-pound beast in one piece. More than that, the behemoth broke the International Underwater Spearfishing Assn. record catch for white sea bass by women’s speargun by weight. Hara hardly rested on her laurels before spearing another world-record-breaking kelp bass just one month later.

Mitsuki Hara assesses the conditions as she heads out to go spearfishing Dec. 8 off the coast of Los Angeles County.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“She’s one of the bright new faces of California spearfishing,” says Lance Lee Davis, a record-holding freediving and spearfishing instructor.

“It’s an incredible accomplishment,” says Addrianna Reitenbach, president of SoCal Dive Babes — an organization for women in spearfishing and freediving. “She caught the white sea bass on a shore dive, which means she had to carry that thing up the cliffs. The world record requirements also don’t allow for anyone to help you.” This means that Hara had to catch the fish in 60-degree water with all her gear — a 10-pound weight belt, snorkel, fins and 2-pound EduSub speargun.

Even more impressive is that 26-year-old Hara looks nothing like the typical spearfisherman. She’s a wispy 5-foot-1 and 105 pounds. That makes operating a speargun underwater a challenge, as it takes significant upper body and back strength to load. “The gun I use is almost my height,” she explains. “It’s so hard to handle that I have a Power Tower [a fitness apparatus used for building muscle strength using body weight] in my living room to do pull-ups every day.”

Hara is part of a movement of local female spearas — slang for female spearfishers — dedicating themselves to engaging with the abundance of the Pacific Ocean they live along.

The rise of spearas (and sustainable fishing)

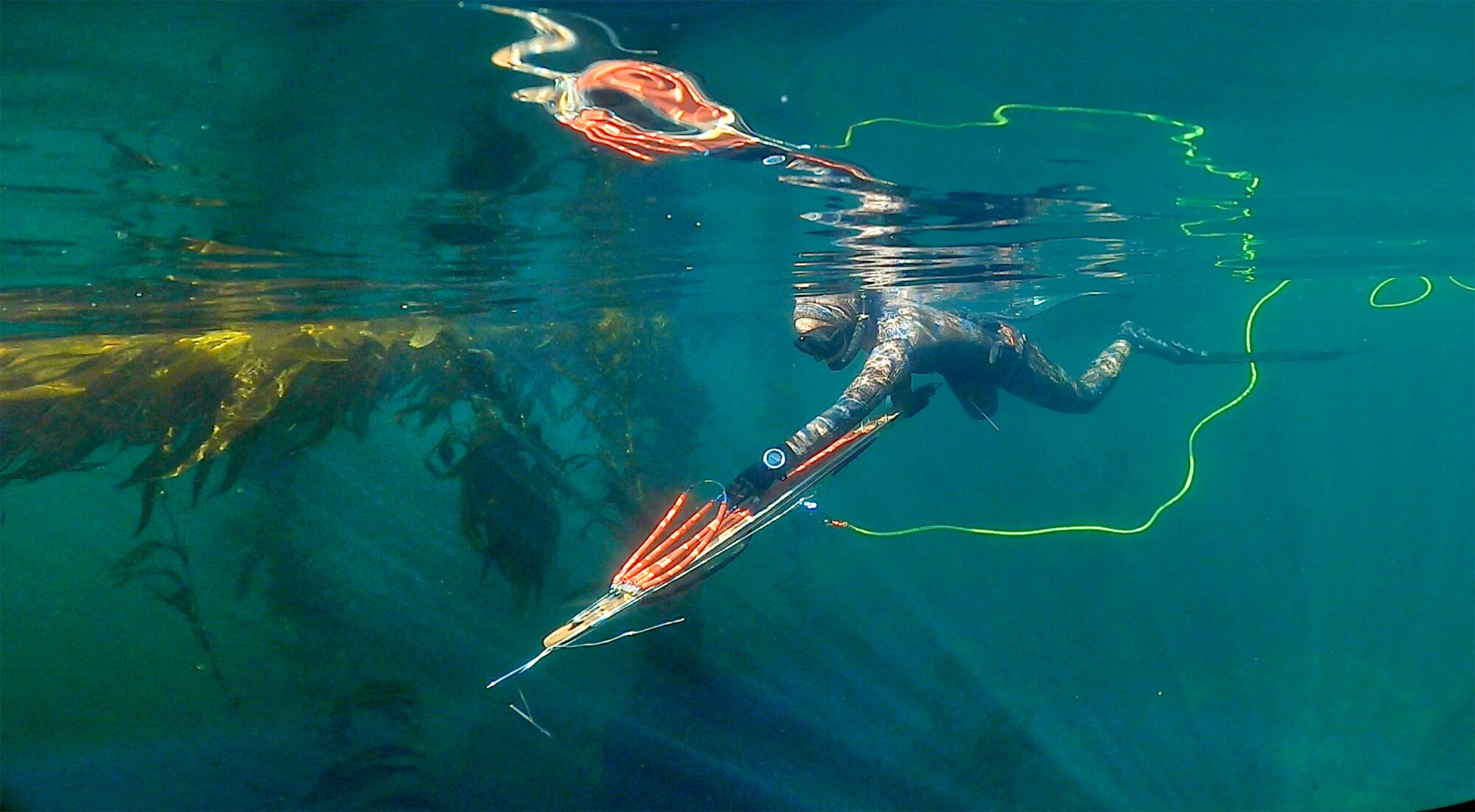

Mitsuki Hara dives deep beneath the kelp while spearfishing off the coast of Los Angeles County.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“There has been a big shift in the demographics of spearing here in L.A.,” says Davis. “I’m teaching many more female environmental and sustainability-driven spearas rather than testosterone-driven male spearfishers.”

Additionally, the Los Angeles Fathomiers, one of the oldest spearfishing clubs in Southern California, reports eight of its roughly 30 members are women — up from just three in 2016. “We also have more women applying for world-record catches on the [International Underwater Spearfishing Assn.] website than in previous years,” says Sheri Daye, the organization’s former president. The founding of SoCal Dive Babes in 2020, in addition to the pandemic and the need for socially distanced activities, has contributed to a noticeable increase of spearas in Southern California, explained Reitenbach. It’s a small but passionate community.

Mitsuki Hara loads her spear while spearfishing off the coast of Los Angeles County.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

These spearas also are part of a growing push around the world for locally caught seafood harvested sustainably — without threatening the ecosystem, other wildlife or the stability of the caught species. Although California is a top seafood exporter with abundantly delicious marine life, it imports most of its consumed seafood — approximately 70% to 85% of the seafood Americans consume is imported, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Hara is a proponent of this view too, celebrating the abundance of her local bounty in a March Instagram post. In the image, she’s grinning ear to ear while sitting next to her husband on a boat, their bodies covered in 28 California spiny lobsters. Hara believes Californians should eat these local creatures instead of importing Maine lobster.

Mitsuki Hara displays California sheephead she caught while spearfishing.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

But it’s not just fishing locally that matters. Spearfishing can be harmful if not approached with a sustainability mindset. Hara explained, “The spearfishing community has many unspoken rules for protecting the fish population.” For example, spearas guard dive spots where they scored their prize fish, to “avoid attracting too many people to a specific location, possibly resulting in marine resource exhaustion.” Also, Davis says, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife “is one of the most tightly regulated fisheries in the world. Basically, if it’s a legal catch in this state, you can consider it sustainable.”

When practiced mindfully, spearfishing can be an alternative to line-caught fishing as there’s minimal by-catch — accidentally catching and killing other species in fishing nets. Also, no bait is used in spearfishing, and there is no residual tackle and fishing net debris. “I can carefully select and shoot only the fish I want to eat,” explains Hara.

Using every bit, down to the bones

Hara used every bit of the 73.4-pound white sea bass — “WSB” to spearas — down to its bones. Shortly after the catch, local artist Dwight Hwang, who has a cult following among restaurateurs and art collectors, memorialized her prize fish. Using the 19th-century Japanese art of gyotaku, Hwang carefully brushed an onyx pine soot and water calligraphy ink onto one side of Hara’s WSB. Next, he delicately pressed the fish onto a piece of washi paper to create a lifelike print to commemorate her catch — honoring the food she took from the ocean. The meat of the fish made for weeks of dinners as well as gifts for friends, and the rest went to her in-laws’ wedding venue and seafood catering restaurant.

Mitsuki Hara hunts for fish while spearfishing off the coast of Los Angeles County.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Hara even repurposed the fish’s skull into taxidermy art. “I follow the tradition of itadakimasu, a Japanese belief with roots in Buddhism, which teaches respect for all living things. This thinking extends beyond mealtime appreciating every part of the animal you’re sacrificing,” she explains. For this time-intensive project, she had to carefully deconstruct the fish skull to clean each part separately before using a glue gun to reassemble it.

It was this patient, detail-oriented researcher’s mindset that helped Hara catch the WSB. She says, “Before anyone else started diving this past season, I was already in the water, taking detailed notes and records of ecosystem changes, moon tides, temperatures and times of day the white sea bass were swimming. Often I was diving five days a week. Yes, I was lucky on the day I caught it, but I spent tens and perhaps hundreds of hours in the water stalking this species.”

Inspiring more women to dive

Her mission is to motivate even more spearas to jump into the ocean. “It makes me happy because so many women getting into spearfishing message me frustrated, asking, ‘How you do it? It doesn’t work for me, the gun is too strong, and I can’t load it.’ I have so much to share because I had to figure out unique techniques to compensate for my size.”

Mitsuki Hara adjusts her mask as she heads out to go spearfishing.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Besides strength training, Hara recommends finding a community and mentors. “There are so many people who are willing to help,” she says, pointing to organizations and groups like SoCal Dive Babes, OC Spearos, Fathomiers and more on Facebook and Instagram. “I’ve made lifelong friends from this community. Catching food together creates a special bond, and we often end our dives with a catch-and-cook dinner together.”

Hara met her mentor, Matthew Hoang, on a local catch-and-cook dive, a game-changer for her spearfishing. “Since he took me under his wing, I started seeing a different world underwater, and I suddenly saw more fish, and I even used my muscles and breathed differently,” she says. In fact, they made such a deep connection, the two ended up getting married two years later.

Their wedding was in the ocean at Avalon on Catalina, and her wedding gown was a Riffe International wetsuit. One of their diving friends got her officiant’s license for the occasion. “When it was time for our kiss, we dove underwater with our 30 guests,” she remembers. “Instead of throwing flowers, we threw fish food.”