By treatment, I mean Target. Retail therapy?

On days she feels particularly stressed, Shamita Jayakumar knows the quickest way to ease her mind.

“I’ll just go to Target and wander the aisles,” she says. “So soothing.”

Every other week or so, the 32-year-old tech worker drives to the sprawling location off Jefferson Boulevard in Culver City and zigzags through the cleaning, camping, cooking, book and beauty aisles. She browses for an hour or two, although it’s hard to say exactly how long, because time feels like it stops. Sometimes she leaves with only a few items, but more often than not, she walks in with a list of two or three things and walks out with $200 of merchandise.

Jayakumar shops at Target in Culver City about every other week.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

It clearly says something about the commodification of self-care, she acknowledges, but it’s about more than that too — it’s that the store is big and bright and air-conditioned and she can zone out and wander in a way she wouldn’t feel safe doing at a park. It’s that the layout here in Culver City looks enough like the one back home in Silicon Valley that she flashes back to Target runs with her mom in the ‘90s, and that there are people around you but no pressure to talk to them.

“My own self-care day,” she calls it.

She’s among a cohort of Gen Z, millennial and Gen X women who view frequent trips to the cheap-chic retailer less as a weekly chore than as a therapeutic experience of sorts — alone time like you might get while going on a solo hike or getting a massage, but under the guise of errands so they’re easier to carve out with some frequency.

“They understand how the consumers are using their store — using it as this slight escape,” Justine Farrell, associate professor and chair of the marketing department at the University of San Diego’s Knauss School of Business, said of Target.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

The brand’s marketing has long portrayed the retailer as a place to get stylish stuff without breaking the bank, Farrell said, noting that while some competitors prioritize cheapest-prices-here advertisements, Target focuses on a shop-here-be-chic message buoyed by years of collaborations with high-end fashion designers and brands such as Isaac Mizrahi, Anna Sui and Missoni.

And the stores themselves are designed to alleviate stressors, Farrell said, noting wide aisles to prevent cart jams, departments that flow into one another to subconsciously guide your wandering and the addition in recent years of in-store Starbucks locations.

“You have your coffee as you meander,” Farrell said. “It becomes more of an experience, versus, ‘Here is my list, let me get in and get out.’”

Retailers have long searched for ways to capitalize on the national mood: In the 1960s and ‘70s, Madison Avenue cashed in on the counterculture to sell everything from cereal to cigarettes; after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, companies of all sizes pumped out patriotic ads, including a General Motors commercial urging people to “keep America rolling” by purchasing a new truck.

So, it’s not surprising that during perhaps the most collectively stressful slice of modern American history — Google searches for “self-care” spiked drastically during the first pandemic lockdown and are even more frequent now — retailers have tapped in to that anxiety.

Jayakumar shops for Halloween items at Target. She browses for an hour or two, although it’s hard to say exactly how long, because time feels like it stops.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

The multibillion-dollar self-care industry has not only spawned hundreds of new companies and Etsy entrepreneurs selling “NORMALIZE THERAPY” and “Self-Care Snob” T-shirts, but has also influenced merchandise trends at long-established retailers like Target, whose aisles began to be stocked with titles such as “Self-Love Workbook for Women,” as well as items labeled as “Self-Care Sunday Ideas,” including a yoga mat, a “GOOD VIBES” sweatshirt and a “ME TIME” cup.

But beyond its merchandise, the brand has long worked to cultivate an image as a “happy place” — a phrase the company uses in corporate blog posts and on gift cards.

“We care about delighting our guests,” the company’s chief executive said on a quarterly earnings call in March, during which another top executive said that Target had long been viewed as “a destination, an escape.” In a written response to questions, Cara Sylvester, the company’s chief guest experience officer, said that the happy-place ethos doesn’t happen by chance.

“We build our entire experience around how we’ll make our guests feel when they shop at Target,” she said.

And it’s served the company well, said Neil Saunders, a retail analyst at GlobalData Retail who has studied Target for more than five years.

“Its growth has been quite extraordinary in the past few years, and a lot of that comes down to them refurbishing stores,” Saunders said. “It’s made Target a destination for people looking to treat themselves.”

This summer, after a customer tweeted about going to Target to buy a bathing suit whenever they feel sad, the official Target account replied to the tweet: “i call that ~ self-care ~.”

Indeed, the escape-to-Target trend has sparked hundreds of TikTok posts and tweets — “I need to go to therapy soon, and by therapy I mean Target,” one person wrote — as well as an essay about the store alleviating an author’s anxiety and an entire subgenre of memes about people going to the store for a toothbrush and walking out with $200 of merchandise, a phenomenon dubbed the “Target Effect.”

“It’s ‘Breakfast at Target.’ You go and just browse.”

— Marylyn Davis

One morning in August, after an exhausting shift at work, Viviana Gonzalez tweeted that she was headed to Target for self-care. She punctuated it with a smiley-face emoji surrounded by three tiny hearts.

The 20-year-old from Bakersfield often starts her trips with a black tea lemonade from Starbucks before meandering the aisles, always checking out the Lego section for the sake of nostalgia. She roams around, decompressing from working the overnight shift as a case manager at a domestic violence shelter.

“I feel like anything can be self-care,” Gonzalez said, “as long as you’re doing it for yourself.”

Jayakumar calls her trips to Target “my own self-care day.”

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

That’s precisely the way to look at it, said Desiree Rew, a clinical social worker in Long Beach who developed a curriculum around self-care and sometimes offers seminars on the topic.

The 52-year-old devised an acronym, SMART, arguing that, to be a reliable part of your tool kit, the practice needs to be sustainable, manageable, accommodating, relaxing and thrilling. Forking out cash for a massage or vowing to meditate every morning will probably violate the first two letters, she said, but something like a periodic Target run likely will not.

“If it brings you joy to do it, that’s your self-care,” Rew said, adding that it doesn’t bother her to see companies capitalizing on the trend. Something small like seeing a “GOOD VIBES” sweatshirt at the store, she said, can help people set new intentions after the collective trauma wrought by the pandemic.

“Yes, they want good vibes, we’ve been surrounded by bad vibes.”

Marylyn Davis’s foray into the world of self-care retail began with her experiences working at a string of start-ups and small businesses.

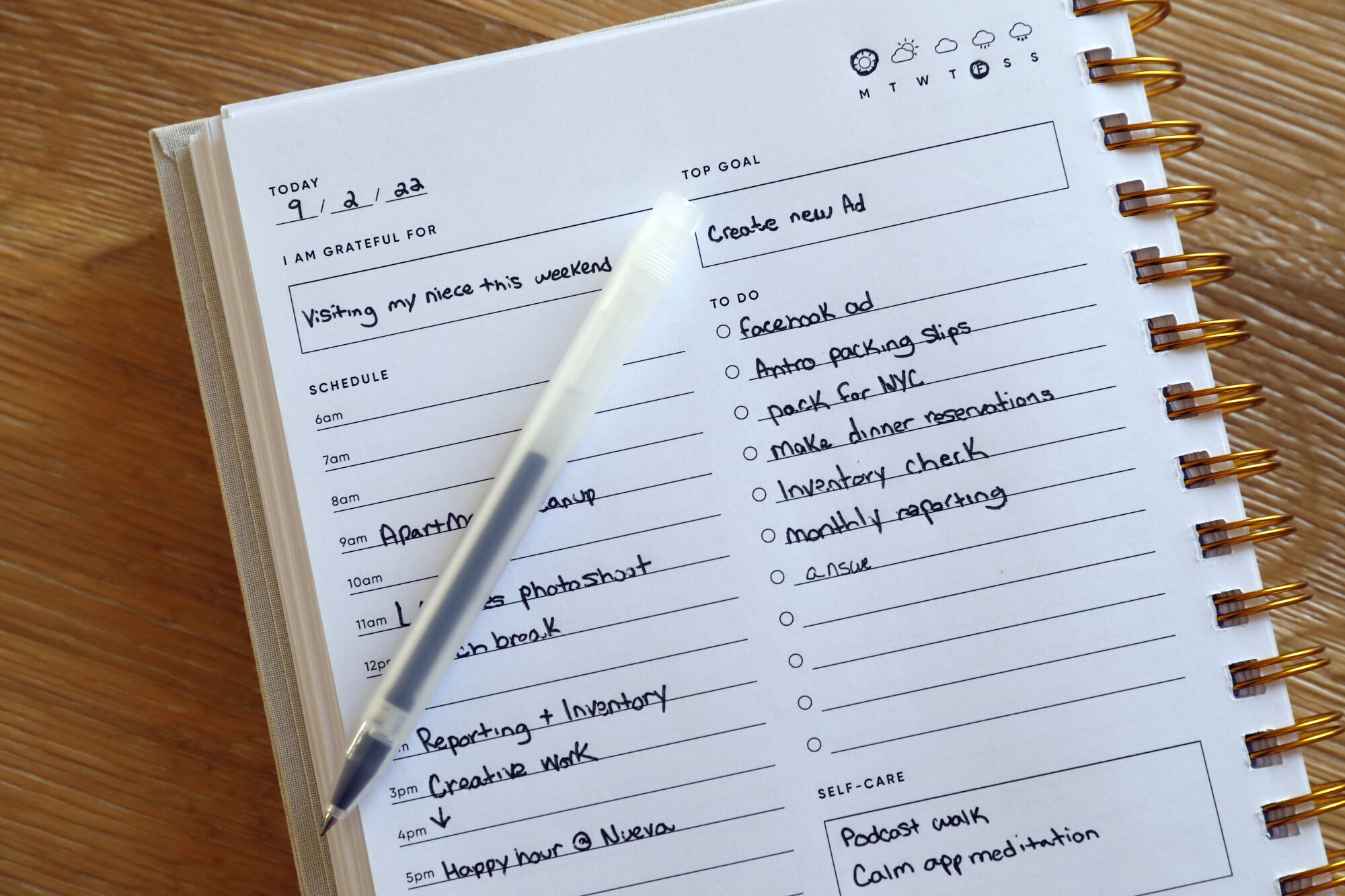

Everyone seemed to eat lunch at their desks, and walking outside for fresh air was frowned upon, she said. Even after she took a remote position, she struggled to separate her work hours from her time off the clock. Perpetually drained, Davis, 31, searched online for a daily planner that incorporated space for goals beyond just work, things like checking in with friends, taking time for gratitude and spending time outdoors.

She couldn’t find any, so she designed her own “self-care planner,” and before long a buyer for Nordstrom noticed her company’s Instagram and contacted her. Her company, Simple Self, has since expanded, now selling on Amazon and in Anthropologie stores, and she’s begun to notice a broader cultural shift away from the go-go-go mentality.

“Maybe back in 2018 it was frowned upon that I’d go get lunch away from my desk; now it’s a good thing,” said Davis, who mentions that the Target-run-as-self-care concept resonates with her and that a friend recently compared it to the window shopping scene along Fifth Avenue in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

“It’s ‘Breakfast at Target’,” Davis said with a laugh. “You go and just browse.”

Marylyn Davis is the founder of Simple Self, an L.A.-based company that creates self-care planners. Her daily planners incorporate space for not only work tasks, but other facets of life, such as making time to call friends, plan meals, exercise and more.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

A few weeks earlier, Jayakumar drew the same analogy to the 1961 classic film, saying that the thought of visiting Rodeo Drive — L.A.’s version of Fifth Avenue — sounded dreadful.

“I’d never go look at stuff I can’t afford, that’s not therapeutic,” she said. “But at Target I can see a little face mask and buy it.”

On a recent weekday afternoon, she pulls into the Target parking lot in Culver City in her Tesla Model 3. (The first thing under the “pro” column of the list she made before she and her boyfriend bought the car was that she could charge it at Target.)

She sets her purse in a cart and heads to Aisle F66 — her go-to starting point: cleaning supplies — where she scans for a specific Dawn shower cleaner she saw someone rave about on TikTok. Next, she browses through home goods, where a woman who appears to be in her 50s is examining a set of two-toned stoneware bowls.

“What do you think of these?” the woman asks.

“They’re really pretty,” Jayakumar responds, saying they’d be perfect for serving gazpacho at a dinner party she has coming up.

“I like them for cereal.”

“Yeah, those are good cereal bowls.”

The woman, who mentions that she is restocking her cupboard after letting her ex take all the dinnerware, pivots to sniff a candle and the two women split in different directions. No goodbye necessary — just the type of friendly, low-stakes conversation Jayakumar loves to have with strangers at Target.

She picks up a set of white towels with light blue detailing, but decides to add them to the mental list of things she’ll buy when she and her boyfriend eventually move out of their one-bedroom apartment in Santa Monica.

“One day,” she says, sighing. They’ve made offers on 23 homes in the last two years, sometimes offering 20% more than the asking price, she said, but they keep losing to all-cash buyers.

As the earworm melody of MGMT’s “Electric Feel” hums softly from above, Jayakumar heads to the camping section, which she loves, even though she does not love to camp. She picks out a backpack cooler, which she’ll use to chill wine at an upcoming picnic-and-movie outing at Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

“Maybe back in 2018 it was frowned upon that I’d go get lunch away from my desk; now it’s a good thing,” says Davis.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

In the kitchen section, where she’s made a game of scouring the evolving selection of ever-smaller egg-frying pans, she notices a $24.99 teal-colored contraption that makes mini egg bites and it cracks her up. She buys it as a Secret Santa gift and heads to her favorite part of the store — the “Minis” section, as she calls the bins filled with tiny packages of beauty products.

As she puts a cucumber-and-mint scented deodorant about the size of a matchbook into her cart, she starts to laugh, noting that whoever came up with this section is a marketing genius.

“You’re making someone pay for a trial size,” she says. “They used to give these out for free.”

Nearby, she notices a back massager and wonders if it will help with her nagging aches, one of many health issues she began to notice two years ago. After what felt like a million appointments, she was recently diagnosed with intracranial hypertension, she says, and will eventually need surgery to relieve pressure on her brain.

“It’s been a nightmare,” she says, as she sets a container of melatonin chews into her cart. “So that stress has caused me to come to Target more and more to relax.”

At the cash register, a Target employee — a baby boomer with a pixie haircut and a wide smile — greets her and compliments the backpack cooler, saying it’d be perfect for a picnic at the Hollywood Bowl.

Jayakumar tells her that she’s going to see Diana Ross at the Bowl in a few days and the employee shares that she hopes to see Usher in concert soon, although the tickets are pricey and her husband isn’t a big fan. Jayakumar suggests that she show him Usher’s Tiny Desk Concert on NPR — it’s amazing, she tells her.

“Maybe that’ll change his mind,” the employee says, her eyes sparkling.

The cashier scans the final item and the total pops up on the screen. She came in for shower cleaner and a cooler and is leaving with $271.01 in merchandise — and a mellowed mood.