Theresa Runstedtler talks about Kareem and the 1970s NBA in her book “Black Ball.”

On the Shelf

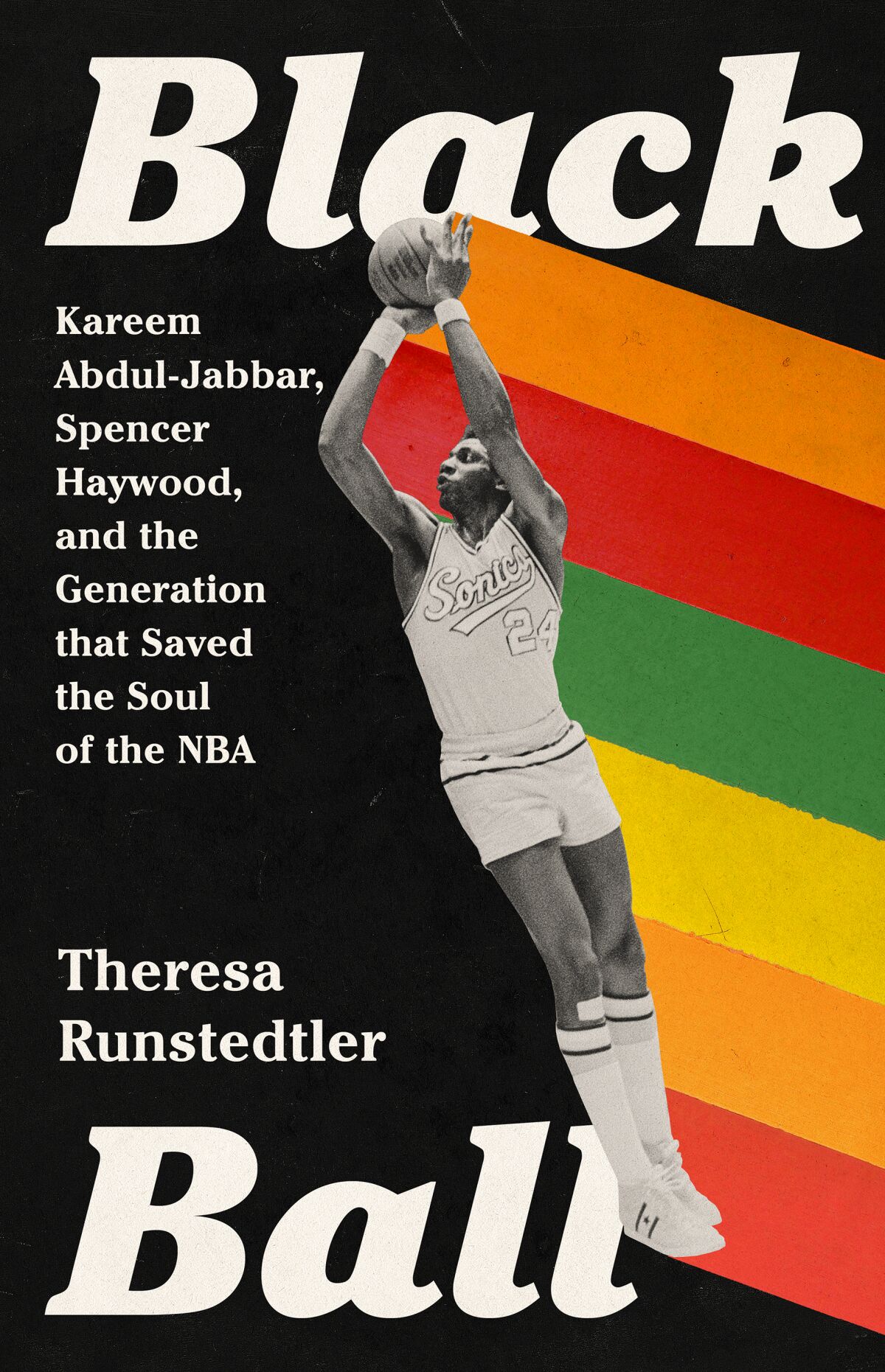

Black Ball: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Spencer Haywood, and the Generation That Saved the Soul of the NBA

By Theresa Runstedtler

Bold Type: 368 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Young Black men on drugs! Starting fights! Looking to get paid! This was the collective NBA boogeyman of the 1970s and early ‘80s, a transitional period in professional basketball and in society. As a majority-Black league embracing a flashy style of play and reflecting the gains of the civil rights movement and Black Power, the NBA entered a new era of visibility. The stars expected to be compensated and taken seriously as human beings. Not surprisingly, the backlash was considerable — among management reluctant to give up absolute control and among a largely white fan base resentful of these new players pulling in big piles of cash (which, by today’s standards, would appear to be a pittance).

Oscar Robertson, who fought to remove the reserve clause from NBA contracts, is swarmed by fans of as he searches for his luggage at the airport in Milwaukee in 1971.

(Paul Shane / Associated Press)

This is the world of “Black Ball: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Spencer Haywood, and the Generation that Saved the Soul of the NBA,” Theresa Runstedtler’s wise, engaging and frankly overdue survey of a crucial moment in sports history. This is primarily a story of labor and race and America, told through the prism of a league approaching but not yet arriving at its current level of mass-produced, carefully packaged popularity. It’s a story of anti-drug hysteria set in the Me Decade of rampant cocaine use and of a product struggling with its close proximity to the streets. And it’s a study of institutionalized racism in a culture changing so fast that its old, white guard could scarcely keep up.

“This is the same period in which the Bronx was burning, and the quote-unquote inner cities were recovering from all of the uprisings that happened in the mid-’60s forward,” Runstedtler says from her home office in Baltimore. “There is this anxiety about young Black men being given too much freedom — that this probably is going to lead to some kind of violence … or criminal activity.”

Runstedtler, a professor and historian of race and sport at American University, took a circuitous but illustrative path to her latest subject. An Ontario native, she was a member of the Toronto Raptors Dance Pak in the ‘90s. A new expansion team, the Raptors began with a youthful startup approach under Black co-founder, general manager and former NBA star Isiah Thomas.

“We didn’t look like the typical NBA dance team,” Runstedtler writes. “We were more urban athletic than sexy glamour. There was no fixation on weight. Paying homage to African American hip-hop culture, we wore coveralls, bandannas, and sequined jerseys, and we danced to the latest rap and R&B hits.”

But then the team was sold to the more corporate-minded Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment. The dance crew changed: “skinnier, whiter, blonder.” The hip-hop was replaced by Motown. As Runstedtler writes, “It became apparent that we were performing for the wealthy white season-ticket holders on the floor rather than the regular (often nonwhite) fans in the nosebleeds. In some respects this book has been more than two decades in the making — a way for me to make sense of what I became a part of in the late 1990s.”

After studying history and African American studies at Yale, Runstedtler began thinking about and researching what are sometimes called the NBA’s “dark ages.” The plotlines are many.

There’s superstar Oscar Robertson’s legal battle against the NBA’s option (or reserve) clause, which bound a player to one team for life at the team’s discretion. There’s the arrival of the upstart, razzle-dazzle ABA, which briefly gave players more choices — a freedom the NBA feared so much it forced a merger in 1976.

There’s also Abdul-Jabbar, the cerebral UCLA and Lakers great, who baffled the media by refusing to play its game of feigned politeness and canned answers. There’s the hysteria over players’ use of cocaine, a drug popular among many people with disposable income in the ‘70s and ‘80s, which somehow terrified and enraged the league and the media when rich Black guys were indulging. (An innuendo-driven Los Angeles Times article helped drive the panic).

‘Black Ball’ author Theresa Runstedrler is a historian of race and sports.

(Britt Ecker-Olsen Photography)

Runstedtler makes it clear that she’s aware the NBA wasn’t angelic in the ‘70s. “I’m not saying in the book that nobody was doing coke, but that we need to think about that as a racialized narrative, a moral panic that became this major story about Black basketball players in the years leading up to what eventually becomes a crack-cocaine crisis,“ she says. “Everybody just falls into lockstep and says, ‘Yes, we must punish these guys. We must control them. We must surveil them using police.’” It’s the same kind of rhetoric that was used in the increasingly draconian War on Drugs.

The stroke of honesty that guides “Black Ball” is its insistence that our perceptions of race affect how we view the game, and that you simply can’t divorce sports from the times in which they are played — and the audiences for whom they’re played. Today’s NBA has mastered the art of having it both ways, harnessing the league’s cool and its Black style without ruffling too many feathers. (This is largely the subject of another fine basketball book, Pete Croatto’s “From Hang Time to Prime Time”).

“Black Ball” is a timely read at a moment when professional athletes are more outspoken than ever on social issues, and when it’s clear that sports and society are inextricably linked. Without the advances chronicled here it’s hard to imagine, for example, the NFL pledging $250 million to combat systemic racism (after basically blackballing Colin Kaepernick for his silent sideline protests against police brutality).

Members of the Milwaukee Bucks and the Boston Celtics kneel around a Black Lives Matter logo before the start of an NBA basketball game in 2020 in Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

(Ashley Landis / Pool / Getty Images)

It’s also important to note that NBA players have been told to “shut up and dribble,” or some equivalent, for decades. Runstedtler represents a school of sportswriting and scholarship that recognizes the most important action takes place off the court.

Chris Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.